You are in :

Ancient Environments

Cretaceous to Late Miocene

Environmental conditions during the Cretaceous were very different from today and sea levels were significantly higher. At times, as little as eighteen per cent of the Earth's surface was land, compared to twenty-eight per cent today. In addition, temperature variations between the North and South poles and the equatorial regions were minimal compared with the vast contrasts observed today.

Evidence of these ancient environments in south-east Arabia is supported by fossils found around Jebel Hafit and in Abu Dhabi's Al Gharbia (Western) Region.

They include marine organisms that flourished in Cretaceous seas and a range of Asiatic, European and African mammals, reptiles and fish that inhabited the river valleys and plains during the Late Miocene.

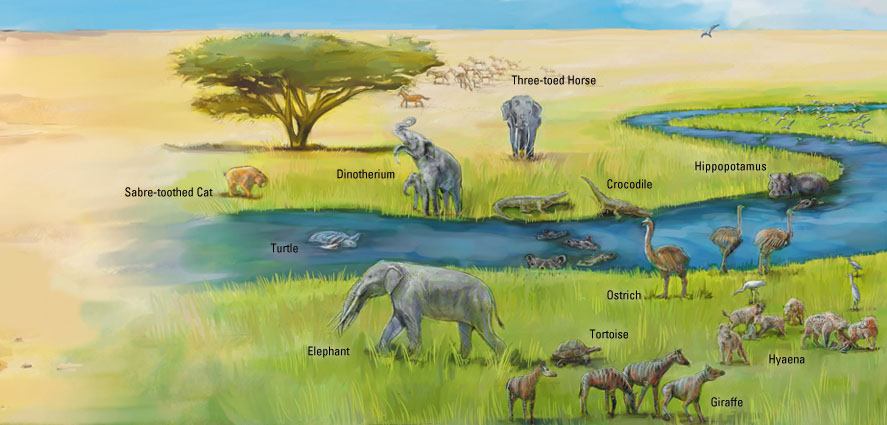

However, the largely maritime world of the Cretaceous period changed dramatically by the Late Miocene. Fossils discovered in Al Gharbia indicate a dry savannah-type environment, including shallow rivers that supported a range of animals. Conditions were similar to the savannahs of present-day East Africa, which today sustain the largest concentrations of land mammals on Earth.

Gathering the Evidence

Since the 1990s, fieldwork in Al Gharbia has produced a wealth of fossil evidence about the savannah ecosystems that once existed. The fossils, between 8 and 6 million years old, were found in a geological stratum now called the Baynunah Formation.

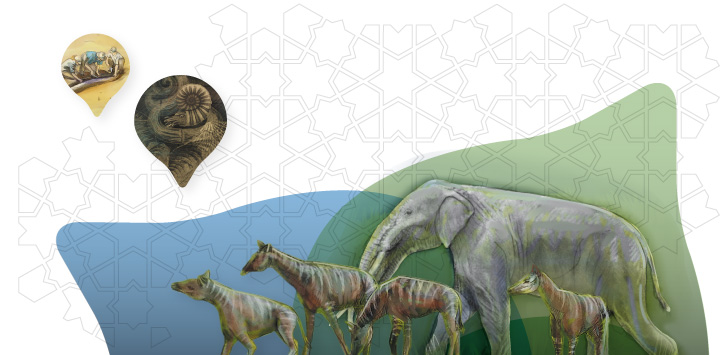

Baynunah fossils feature Asiatic, European and African species of hoofed mammals (including antelopes, horses and hippopotami), non-hoofed mammals (such as elephant and a primate) and non-mammals (including turtles and fish). Notable discoveries include a new species of gerbil (Abudhabia baynunensis), and a three toed horse, (Hipparion abudhabiense).

Among recent significant discoveries are extensive remains of the primitive elephant (Stegotetrabelodon syrticus), a partial skeleton of a giraffe (Palaeotragus germaini) and ancient lake-beds preserving the footprints of wandering elephants. The Baynunah Formation is rich in fossil eggshells from Diamantornis laini, a large flightless bird related to today's ostriches.

Research began in the late 1980s, initially undertaken by Yale University, the Natural History Museum in London, the former Department of Antiquities and Tourism in Al Ain, and later by the Abu Dhabi Islands Archaeological Survey (ADIAS). Since 2006 it hasbeen undertaken by a joint team from Yale University and the Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage (ADACH).

Further research will expand the already extensive and diverse list of species that once thrived on Abu Dhabi's rich savannahs.

Evidence of Early Life

Cretaceous - 145.5–65.5 Million Years Ago

The Cretaceous period was especially significant for the Emirate and the Gulf region since more than 50% of the world's oil reserves were formed at this time, of which some 75% are located in and around the Arabian Gulf.

The Cretaceous period is remarkable for its exceptional and unique life forms. During this period, dinosaurs dominated the earth before suddenly disappearing in a great episode of extinction. Modern mammal groups evolved, including animals such as primates, pigs, cows, cats, dogs and rodents, as did marsupials such as kangaroos and koalas. In addition to ancient plants such as ferns, conifers, Cycads and Ginkgoes, the Early Cretaceous witnessed the first appearance of Angiosperms (a group that includes flowering plants and grasses). This led to an increase in the abundance and diversity of insects that acted as essential pollinators of the expanding flowering plant communities.

When the Rivers Flowed

Late Miocene – 8–6 Million Years Ago

Imagine the ancient environment of Abu Dhabi: in the rivers, catfish search for freshwater mussels as barbel fish glide through the shallow waters. In the muddy backwaters, hippos keep cool during the fierce midday heat while 2-metre-long crocodiles bask along the riverbanks. Nearby, egrets and other birds wade in the shallows looking for small fish.

The peace of the river basin is periodically disturbed as herds of large animals push towards the thirst-quenching waters. These include primitive elephants with 2 sets of tusks, 1 in the upper jaw and another, shorter, in the lower.

In a nearby thicket, a sabre-toothed cat waits to stalk its prey of abundant gazelle or larger antelope grazing on tender shoots following seasonal rains. On the open savannah, herds of Hipparion – a three toed relative of the horse – are grazing. Taller shrubs are browsed by a shorter relative of the modern giraffe.

Large antelopes could fall victim to predators such as the sabre-tooth cat, but elephants have little to fear on the open plains.The hyaena, an opportunist feeder, constantly searches for prey such as a pig or easier meals like an abandoned carcass or the eggs of a large, ostrich-like bird.

Although the animals appear primitive, the scene is strangely familiar. These savannahs of ancient Abu Dhabi with their unique fauna and flora were destined for extinction as the climate became drier and less hospitable. The rolling, verdant grasslands with large herds of grazing animals, flowing rivers and intermittent forests were gradually replaced by the desert dunes and barren sabkhas of today's Emirate. Only highly specialised plants and animals well adapted to these harsh, water-constrained conditions would survive.

Under the Sea

The Hajar Mountains originated during the Cretaceous. Composed of ophiolite rocks originally deposited in deep marine conditions, they were uplifted by colliding plates and created a chain of islands. A shallow warm sea lapped up against the islands of limestone rocks now known as the Simsima Formation. Around the islands, fossilised relics of early life abound where the coarse beach gravels and sands were once deposited. In more protected bays, colonies of corals and molluscs known as rudists lived close to the shore while sandy bays sheltered burrowing bivalves and marine snails.